Pre-C19 Stained glass in France

Origins and the Birth of the Gothic Window (12th century)

France was the cradle of the Gothic cathedral and, with it, the birthplace of stained glass as a monumental art form. By the early 12th century, the theological writings of Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis had articulated a vision of divine light (lux nova) as the medium through which the material world could reveal spiritual truth. In the rebuilding of the Abbey of Saint-Denis (c.1140–1144), Suger's vision was made visible: coloured light flooded the interior through vast expanses of stained glass, transforming stone architecture into a radiant symbol of celestial harmony.

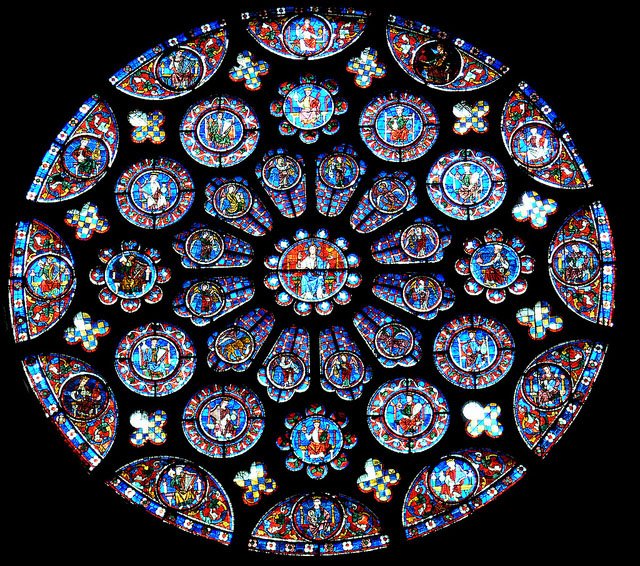

The stained glass of Saint-Denis, followed shortly by the glazing of Chartres, Le Mans, and Soissons, represents the foundation of the Gothic aesthetic — a synthesis of structure, light, and theology. These early windows employed deeply coloured pot-metal glass — cobalt blues, ruby reds, emerald greens, and purples — arranged in small, complex pieces held within dense networks of lead cames. Figures were monumental, framed in medallions or quatrefoils, their forms outlined in black vitreous paint and animated by touches of yellow silver stain. Each panel formed part of a vast biblical and symbolic programme, designed to instruct, inspire, and envelop the viewer in a vision of divine order.

The High Gothic: Chartres and Beyond (13th century)

The early 13th century marks the high point of French Gothic stained glass. Nowhere is this more powerfully expressed than at Chartres Cathedral (c.1200–1235), whose nearly 2,600 square metres of surviving glazing constitute the most complete ensemble of medieval stained glass in existence. The intense ultramarine of Chartres blue, the rich ruby reds, and the intricate iconographic cycles — from the Passion to the Labours of the Months — defined a standard emulated across Europe.

Other great glazing campaigns followed: Reims, Amiens, Bourges, and Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. The latter, commissioned by Louis IX between 1242 and 1248 to house the Crown of Thorns, epitomises the Gothic ideal of the “house of glass” — its walls seemingly dissolved into vertical veils of coloured light. Here, stained glass became both architectural structure and theological statement: the visible medium of the heavenly Jerusalem.

Technically, this period saw refinements in glass-blowing, painting, and composition. Glaziers achieved greater tonal control through the layering of flashed glass (thin coatings of colour fused to clear glass) and the precise use of silver stain to achieve golden hues. The craft was increasingly specialised, with dedicated ateliers supplying cathedrals and monasteries throughout the realm.

The Rayonnant and Flamboyant Periods (14th–15th centuries)

As Gothic architecture evolved toward greater delicacy and linearity, so too did its stained glass. The Rayonnant style of the 14th century, exemplified at Saint-Ouen in Rouen and Saint-Urbain at Troyes, emphasised lighter tonal harmonies and more open compositions. Figures became more naturalistic, their gestures graceful and humanised. The once-dominant deep blues and reds gave way to broader areas of white and pale glass, enhancing luminosity within increasingly elaborate traceries.

By the 15th century, the Flamboyant Gothic introduced even greater intricacy. In regions such as Normandy, Champagne, and Burgundy, workshops developed distinctive local idioms, combining refined draughtsmanship with sumptuous colour. The iconography of the period reflected the devotional currents of late medieval piety — the cult of the Virgin, the Passion, and the saints — as well as the growing importance of donor portraits and heraldic imagery. The glazing of Rouen Cathedral, Évreux, and Troyes stands among the finest examples of this mature Gothic style, marked by elaborate canopy work and refined storytelling.

The Renaissance and the Transition to Pictorial Glass (16th century)

The early 16th century ushered in profound artistic change as Renaissance ideals of perspective, proportion, and classical form spread north from Italy. French glass painters, particularly in the Loire Valley and Champagne regions, absorbed the innovations of contemporary painting and engraving, producing works of remarkable naturalism and narrative clarity.

Workshops in Troyes, Rouen, Chartres, and Le Mans became renowned for their mastery of the new style. Artists such as Valentin Bousch, Engrand Le Prince, and Jean Cousin the Elder redefined stained glass as a painterly medium, using enamel paints and silver stain to model form, light, and texture with unprecedented realism. Biblical scenes were rendered in architectural or landscape settings inspired by the Italianate vocabulary of the Renaissance. Draperies flowed in rhythmic folds; faces expressed emotion and individuality; perspective opened the pictorial space into deep vistas.

At Saint-Gervais in Paris, Beauvais Cathedral, and Sens, Renaissance glazing became a vehicle for humanist theology and royal patronage. In the Loire Valley — at Tours, Vendôme, and Le Mans — the great families and ecclesiastical patrons commissioned windows to celebrate both faith and lineage. The result was an extraordinary fusion of sacred narrative and artistic innovation, marking the last great flowering of monumental stained glass before the disruptions of the Wars of Religion and the Counter-Reformation.

Legacy and Survival

France possesses the richest corpus of medieval stained glass in Europe, owing to the scale of its Gothic cathedrals and the continuity of ecclesiastical patronage. Despite damage from revolution, war, and neglect, the survival of ensembles at Chartres, Bourges, Troyes, and Paris allows modern viewers to experience the full spectrum of medieval and Renaissance glazing — from the mystical abstraction of the 12th century to the painterly sophistication of the 16th.

Through these centuries, stained glass in France evolved from theological light to pictorial art, from collective devotion to individual expression. Yet its essential purpose remained unchanged: to transform the material substance of coloured glass into an image of spiritual illumination — a vision of faith made radiant in light.