French Designers

Destruction and Dormancy (1789–1830)

The French Revolution marked a decisive break in the long history of stained glass. Centuries of ecclesiastical patronage ended abruptly; countless windows were shattered, removed, or sold as symbols of royal and religious oppression. In the decade following 1789, churches were desecrated, monasteries dissolved, and workshops dispersed. Stained glass, an art rooted in the liturgy and the monarchy, virtually ceased to exist as a living craft.

During the First Empire (1804–1815) and the Restoration, stained glass lingered as a curiosity of antiquarian interest. Isolated artisans, such as Pierre Gaudin and François Ragueneau, produced small heraldic or secular panels, but large ecclesiastical commissions were rare. The craft survived mainly in the restoration of a few historic monuments and through the study of medieval fragments by emerging scholars of Gothic art.

The Romantic and Gothic Revivals (1830–1870)

The revival of stained glass in France was inseparable from the Romantic rediscovery of the Middle Ages and the Gothic Revival in architecture and aesthetics. The July Monarchy and Second Empire witnessed a new enthusiasm for national heritage, led by scholars such as Prosper Mérimée (Inspector of Historic Monuments) and Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, whose restorations at Chartres, Amiens, and Sainte-Chapelle renewed public appreciation for medieval glass.

A decisive moment came in 1844 with the foundation of Adolphe-Napoléon Didron’s journal, Annales Archéologiques, which codified the study and theory of Christian iconography. Didron’s call for a return to the “archaeological truth” of Gothic art inspired a generation of artists and workshops, among them Henri and Alfred Gérente, Claudius Lavergne, and Émile Thibaud, who combined meticulous historical study with technical experimentation.

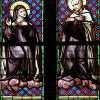

The mid-century revival saw the re-establishment of stained glass as a major component of ecclesiastical architecture. Workshops multiplied in Paris, Lyon, and Chartres, producing both restorations and new cycles for churches built during the Second Empire’s wave of religious reconstruction. The glass of this period is characterised by vivid colour harmonies, careful draughtsmanship, and a scholarly adherence to medieval iconographic models. Yet, alongside this archaeological fidelity, artists such as Lavergne introduced subtle classical and academic influences, reflecting the aesthetic dialogue between Ingres and Delacroix that defined French art of the era.

Industrial Expansion and Regional Workshops (1870–1914)

By the late 19th century, stained glass had become an industry as well as an art. The growth of the rail network and urbanisation brought thousands of new parishes and chapels, each requiring decorative glazing. Major studios such as Lobin (Tours), Gibelin (Orléans), and Fournier (Le Mans) supplied windows across France and the colonies, standardising production through the use of cartoons and pattern books.

At the same time, smaller ateliers, Julien Fournier in Loir-et-Cher, Champigneulle in Paris and Bar-le-Duc, and Rostand in Lyon, maintained a high level of craftsmanship and iconographic integrity. The period also saw increased participation of academically trained artists who designed windows in collaboration with master glaziers, integrating pictorial realism and subtle shading made possible by enamel painting and the refined use of silver stain.

Artistic taste shifted toward softer tones and greater naturalism, aligning with the devotional art of the Third Republic. Windows from this era often depict narrative scenes framed by Gothic canopies, yet rendered with the sentimentality and painterly finish characteristic of Salon art. This synthesis of tradition and modernity culminated in the monumental cycles of the late 19th century, such as Galland and Gibelin’s Life of Joan of Arc (Orléans Cathedral, 1893–95), which combined historical scholarship, national pride, and academic style.

The Interwar and Modernist Generations (1918–1945)

The devastation of World War I brought both destruction and renewal. Churches in the north and east of France, at Reims, Arras, and Soissons, lost much of their glazing, prompting a new wave of restoration and creativity. In the 1920s and 1930s, ateliers such as Mauméjean Frères, Jacques Gruber, and Louis Barillet embraced the aesthetics of Art Deco and Modernism, transforming stained glass into a medium of modern architecture.

In this period, design shifted toward geometric composition, stylised form, and architectural integration. Artists such as Barillet, Le Chevallier, and Décorchemont experimented with dalle de verre (slab glass set in concrete) and etched or plated glass, treating light as a structural and sculptural element. Their work adorned both churches and secular buildings, reflecting the movement’s desire to unite craftsmanship, industry, and contemporary art.

Post-War Renewal and the Spiritual Abstraction of Light (1945–Present)

The Second World War again left thousands of churches shattered. The post-war reconstruction provided an unprecedented opportunity for innovation. Ateliers such as Simon-Marq in Reims and Loire in Chartres became central to the movement to reinvent stained glass for the modern age.

Artists including Henri Guérin, Jean Bazaine, Roger Bissière, and above all Marc Chagall ⓘ brought a new artistic vocabulary to sacred glass. Their work rejected literal narrative in favour of symbolic and abstract expression, focusing on light as a manifestation of spiritual energy rather than pictorial illustration. Chagall’s windows for Metz (1958–68) and Reims (1974), executed by Charles Marq and Brigitte Simon, exemplify this synthesis of modern painting and traditional glasscraft.

By the 1970s and 1980s, French stained glass had re-emerged as an international art form. Artists such as François Taureilles, Jean Le Moal, and Catherine Menu explored abstract or elemental themes, fire, air, earth, and light, reflecting a universal spirituality beyond denominational boundaries. The great historic ateliers, including Atelier Simon-Marq and Atelier Loire, continued to produce both restorations and new works, ensuring a living continuity between tradition and modern innovation.

Legacy

From the ashes of the Revolution to the glass walls of the modern cathedral, the history of post-Revolution stained glass in France is a narrative of resilience, renewal, and reinvention. Rooted in the medieval synthesis of light and faith, it adapted to successive cultural, political, and artistic transformations, Romanticism, industrial modernity, and post-war abstraction, while maintaining its essential vocation: to mediate between architecture and the transcendent.

Today, the stained glass of France stands as both heritage and living art, a dialogue between centuries. Its evolution from Didron’s archaeological piety to Chagall’s mystical colour charts the enduring power of light as the most eloquent and enduring medium of the sacred imagination.