Luca della Robbia, Cantoria (1431–1438) - Florence

Primary tabs

“Sing to the Lord a New Song”: Luca della Robbia’s Cantoria

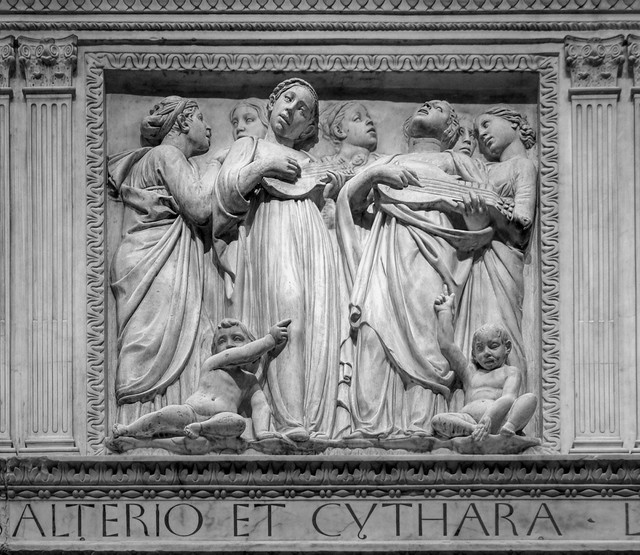

Between 1431 and 1438, the Florentine sculptor Luca della Robbia1 carved in marble one of the most radiant celebrations of music and childhood in the early Renaissance, the Cantoria, or singing gallery, originally made for the north singing gallery of Florence Cathedral.

A Psalm in Marble

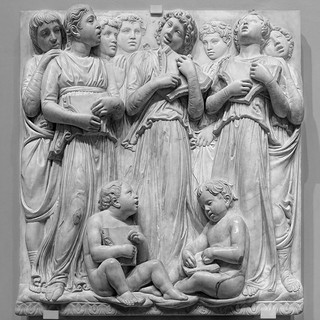

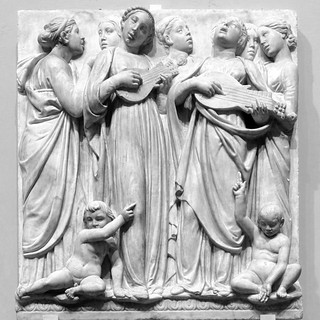

Commissioned to hold the voices of real choirboys during Mass, the gallery itself became a hymn in stone. The inscription that once ran along the gallery’s cornice declares its inspiration: Psalm 150, “Praise Him with the timbrel and dance; praise Him with strings and pipes.” Across eight front panels, arranged in two rows of four, Luca traces a rising hymn of sound and movement: trumpeters and dancers announce the song; girls with hymnals sing in harmony; musicians pluck harp and lute; children play organ and flute; percussionists beat tambourines and cymbals; others dance freely; and, at the end, older youths hold a long scroll, their calm composure restoring stillness after the crescendo of joy.

Unlike the solemn angels of medieval art, Luca’s figures are animated by an inner joy. They move freely, responding to the music that seems to fill their marble stage. The Cantoria is not an image of divine majesty but of human praise, expressed with the unguarded delight of youth.

The Cantoria is both art and theology: a Renaissance vision of cosmic harmony, where faith, music, and human grace join in perpetual praise.

The World of the Choirboys

The Florence of Luca della Robbia’s day was alive with music. The Cathedral maintained choirs of professional singers and boys trained in the city’s religious institutions. Among these were the children of the Ospedale degli Innocenti, the foundling hospital designed by Filippo Brunelleschi and dedicated to the care and education of abandoned infants.2

Boys who grew up at the Innocenti were taught to read, sing, and serve the Church. Records show that they were often sent as choirboys to Florence’s major churches, and even that Brunelleschi himself fostered one of them, a boy named Nanni di Miniato, who became his apprentice.

While no document links Luca directly to the Innocenti, his Cantoria seems to breathe the same civic spirit: the belief that beauty, learning, and piety could be born from the nurture of children. The joyful singers and dancers on these panels may not be portraits, but they belong unmistakably to the Florence of real boys’ voices echoing beneath the Cathedral’s dome.

Art and Humanism

Luca’s work belongs to the early flowering of Renaissance humanism, when artists sought to unite Christian faith with the harmony and grace of classical art.

Luca’s work belongs to the early flowering of Renaissance humanism, when artists sought to unite Christian faith with the harmony and grace of classical art.

The boys of the Cantoria recall ancient reliefs of Bacchic dancers and Roman sarcophagi, yet their meaning is profoundly new. Their youthful bodies express not pagan revelry but innocent exultation before God. Luca achieves this by balancing rhythmic symmetry with natural observation: the bodies are idealized, yet each gesture feels spontaneous, as if caught mid-song.

This blending of antique form and living humanity became one of Florence’s great artistic inventions. In Luca’s panels, the Renaissance ideal of the harmonia mundi — the harmony of the world — finds visual form. The sculptor translates divine order into the rhythm of moving children, whose song and dance mirror the celestial music of creation itself.

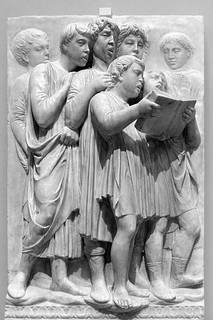

The Two Cantorie

Luca’s gallery once faced another across the Cathedral choir: the Cantoria carved between 1433 and 1439 by Donatello.3 Where Donatello’s reliefs show muscular youths bursting with physical energy, Luca’s are gentler, lyrical, and serene. The two together represented complementary visions of praise: Donatello’s ecstatic vitality and Luca’s contemplative harmony.

Luca’s gallery once faced another across the Cathedral choir: the Cantoria carved between 1433 and 1439 by Donatello.3 Where Donatello’s reliefs show muscular youths bursting with physical energy, Luca’s are gentler, lyrical, and serene. The two together represented complementary visions of praise: Donatello’s ecstatic vitality and Luca’s contemplative harmony.

In 1688, both were removed from the Cathedral, to make room for more singers at the wedding of Prince Ferdinand to Princess Beatrice, eventually they were installed here in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo,4 where their dialogue continues, two voices in the same Florentine hymn to music and faith.

The Children of Florence

To stand before Luca della Robbia’s Cantoria today is to glimpse Florence’s humanistic devotion to childhood. The city’s citizens founded the Ospedale degli Innocenti only a decade before Luca began work on the gallery, moved by the conviction that even abandoned infants deserved nurture, education, and dignity. Under its care, boys were trained in music and crafts, and some, like Brunelleschi’s foster child, entered the workshops that shaped the Renaissance.

The Cantoria can thus be read not only as a theological allegory but as a civic emblem, a monument to Florence’s own children, whose voices filled its churches and whose lives embodied the ideals of charity and learning. The marble singers on these panels may stand for every Florentine boy raised to praise God through beauty.

The Panels

Each of the ten panels forms a stanza in this marble song:

- Singers raise their eyes heavenward, mouths open in praise.

- Dancers move in measured rhythm, their garments flowing.

- Musicians sound cymbals, harps, and small organs.

- In the final panels, the music seems to quicken and dissolve into pure motion, a crescendo of sculpted sound.

Together they form a visual fugue, a harmony of movement and feeling that turns cold marble into living voice. Luca’s carving is so delicate that light itself becomes part of the composition, glancing over curls and folds as if tracing invisible notes across a page.

Boys Singing from a Book: At the gallery’s entrance, choristers lean over an open choir book, marking the beginning of the Psalm. Their earnest concentration signals the start of the marble symphony. Psalm 150: “Sing unto the Lord a new song”

Older Boys Blowing Trumpets, Smaller Children Dancing Below: In top left panel at the front of the cantoria older boys lift their trumpets high, cheeks puffed with breath. Beneath them, smaller children dance in rhythmic counterpoint. Luca della Robbia fuses sound and motion, celestial brass above, earthly joy below, capturing the Psalm’s most exuberant command: “Praise Him upon the high-sounding trumpets.”

Girls Holding Hymnals and Singing: In the second from left panel, a cluster of young girls holds open songbooks, their mouths parted in melody. Their gentle sway contrasts with the vigor of the trumpeters beside them. Each face seems caught between concentration and delight, a vision of innocent devotion, and perhaps of the real choirchildren who once sang in the Cathedral below. Psalm 150: "Let everything that hath breath praise the Lord”

Children Playing Harp and Lute: In the third from left panel, two girl musicians provide the gallery’s quieter counterpoint. One plucks a harp, another strums a lute, while companions listen intently. Here, sound becomes serenity, a reminder that beauty also resides in discipline and restraint. Psalm 150: “Praise Him with stringed instruments.”

Children Dancing with Raised Arms: In the rightmost panel, freed from instruments, the children dance in unison, arms lifted heavenward. Their coordinated movement expresses the Renaissance ideal of harmony between body and spirit. This is Luca’s translation of divine order into human motion. Psalm 150: “Praise Him upon the loud cymbals”

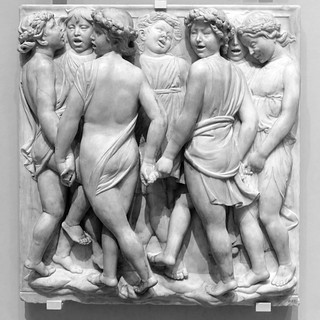

Children Dancing in a Circle: The bottom register left panel, linked hand in hand, the dancers form a ring of rhythmic harmony. Their graceful steps and swirling draperies evoke cosmic order, the planets in divine orbit. Luca turns the Psalmist’s words “Praise Him with timbrel and dance” into a dance of marble, measured yet alive. Psalm 150: “Praise Him with timbrel and dance”

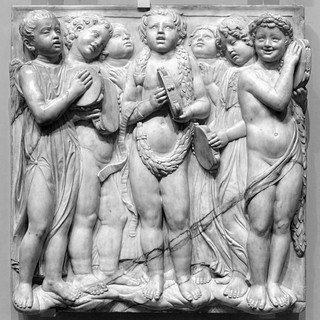

Children with Portable Organ and Flute: The smallest performers add the breath of life to Luca’s marble symphony. One plays a tiny organetto, its pipes rising like miniature columns; another raises a flute. Their puffed cheeks and steady rhythm make visible the invisible, air transformed into melody. Psalm 150: “Praise Him with pipes”

Children with Tambourines and Cymbal: Here Luca della Robbia translates rhythm into marble. Barefoot children beat tambourines in unison, their movements forming a living pattern of sound and motion. The figures’ semi-nude innocence and joyful expression embody sacred music as pure celebration, the harmony of body and spirit praising God together. Psalm 150: “Praise Him with the timbrel and dance.”

Children with Cymbals: The rhythm reaches its peak as children raise their cymbals in jubilant motion. Luca della Robbia translates sound into sculpture—bare feet, swirling drapery, and bright faces convey the pulse of sacred music. This is the Cantoria’s loudest note and its purest joy: the energy of praise turned to marble. Psalm 150: “Praise Him upon the loud cymbals.”

Final Singers Holding a Scroll: Echoing the left panel, these singers close the cycle in perfect balance, the alpha and omega of Luca’s song. The Cantoria begins and ends with music offered in harmony.

- 1. Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore

- 2.

Abandoned Children Of The Italian Renaissance Baltimore John Hopkins University Press 2005.p12.

- 3. Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore

- 4.

The Rise And Fall Of The House Of Medici Allen Lane 1975.p320.