Lavergne, Claudius - Paris

Claudius Lavergne was among the foremost figures of the mid-nineteenth-century revival of stained glass in France, a painter and critic whose intellectual formation under Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and collaboration with Adolphe-Napoléon Didron positioned him at the intersection of academic draughtsmanship, historical research, and religious reform. Born in 1814, Lavergne was trained as a painter in the classical discipline of the École des Beaux-Arts, studying in Ingres’s atelier and absorbing his master’s devotion to linear purity, ideal form, and moral gravity in art.

His transition from painting to stained glass began in 1852, when Didron, then the leading theorist of Christian archaeology and iconography, invited him to design cartoons for new ecclesiastical glazing. The resulting commission—executed in 1854 for the chapel of the Hôpital Lariboisière in Paris—marked the beginning of a career that would last more than three decades. From that point, Lavergne dedicated himself almost exclusively to the art of stained glass, establishing a workshop whose work combined historical fidelity with painterly refinement.

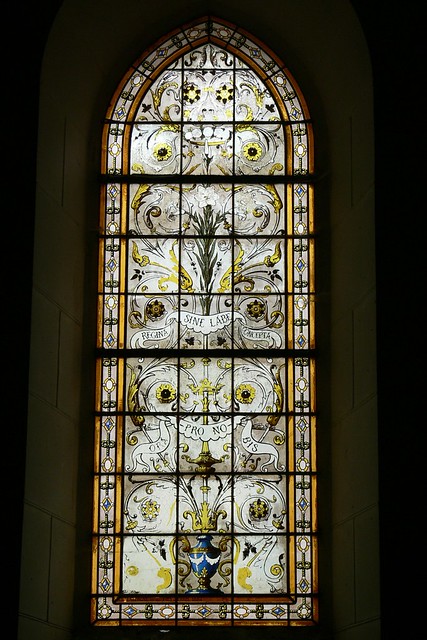

Lavergne’s windows are notable for their strong draughtsmanship, clear modelling, and balanced use of colour. His figures, often monumental and classically posed, reflect the Ingresque ideal of beauty governed by line rather than brushstroke. At the same time, his collaboration with Didron brought a scholarly rigor to his iconography: saints and biblical scenes are conceived with archaeological precision and theological propriety. The result is a style that unites the restraint of classicism with the didactic clarity of Gothic revivalism—an intellectual, rather than emotional, approach to the sacred image.

Beyond his practice as an artist, Lavergne was an outspoken art critic, engaged in the vigorous debates of the 1850s and 1860s surrounding the moral purpose of religious art. In 1861, writing in Le Monde, he published a severe critique of Eugène Delacroix’s murals in the Church of Saint-Sulpice, condemning their “dreadful and animated subjects” and accusing Delacroix of portraying angels as “divine furies” rather than “messengers of piety and peace.” The attack reflected not merely personal taste but the larger opposition between Ingres’s austere neoclassicism and Delacroix’s romantic expressiveness—a conflict emblematic of mid-century French aesthetics. Lavergne’s alignment with Ingres was both artistic and moral: he believed that sacred art should elevate the intellect through serenity and ideal beauty, not stir the passions through violence and movement.

Until his death in 1887, Lavergne remained active as both painter and glass designer, producing windows for churches and chapels throughout France. His son, Noël Lavergne, continued the atelier after him, ensuring the survival of the family’s technical and iconographic traditions into the final decades of the nineteenth century.

In retrospect, Claudius Lavergne stands as a transitional figure—bridging the academic classicism of Ingres and the archaeological piety of Didron, while shaping the visual identity of the French Gothic Revival through glass. His work, austere yet luminous, exemplifies the conviction that beauty, order, and clarity are themselves forms of devotion, transforming light into the disciplined radiance of faith.