Simon-Marq, Brigitte

Born in 1926 into the long-established Simon family of Reims glassmakers, Brigitte Simon-Marq was the daughter of Jacques Simon (1890–1974), whose atelier was already renowned for historic restorations and ecclesiastical commissions. She received her initial training within her father’s workshop, acquiring the traditional skills of glass painting, cutting, and leading that had characterised the family practice since the seventeenth century.

Following a period of study and artistic practice in Paris, she met Charles Marq (1923–2006), a painter and glass artist who shared her commitment to the renewal of sacred art through modern visual language. After their marriage, the couple returned to Reims and in 1957 assumed responsibility for the family firm, marking a decisive moment in Brigitte Simon-Marq’s professional life.

From this point onward, her work developed within the context of the Simon-Marq atelier, where she combined personal artistic authorship with a collaborative approach to making. Working alongside Charles Marq, she played a central role in translating modern painting into the medium of stained glass, uniting artistic invention with rigorous technical execution. This approach enabled close collaborations with leading twentieth-century artists, including Marc Chagall ⓘ, Roger Bissière, and Joan Miró, through which modern pictorial language was successfully adapted to architectural settings.

Among the most celebrated outcomes of this period are the stained-glass windows designed by Chagall for the cathedrals of Metz and Reims, projects that brought international recognition to both the artists involved and to the Reims workshop. In these and other commissions, Brigitte Simon-Marq’s contribution lay in her refined sense of colour, sensitivity to architectural light, and mastery of the technical processes required to realise complex artistic visions in glass.

As an artist, Brigitte Simon-Marq embodied a rare synthesis of tradition and modernity. Her work demonstrates a sustained commitment to craftsmanship, collaboration, and contemporary expression, ensuring the continuity of the Reims stained-glass tradition within the artistic currents of the post-war period. She remained active until late in life, and following her death in 2009, the direction of the atelier passed to her son Benoît Marq, representing the next generation of the Simon family in Reims.

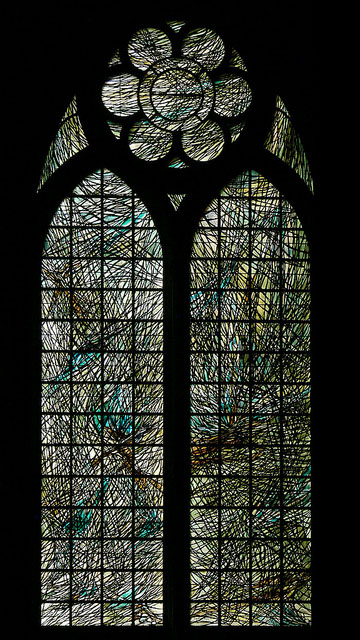

Installed in 1961 in the south transept of Reims Cathedral, near the baptismal font, these three tall lancet windows by Brigitte Simon and Charles Marq marked a turning point in the visual language of sacred glass within a Gothic context. Created under the auspices of the historic Atelier Simon-Marq, the ensemble reflects the radical yet deeply spiritual aesthetic that the couple introduced to mid-twentieth-century ecclesiastical art.

The design abandons traditional figurative representation in favour of an abstract interplay of light, texture, and motion. Each panel is constructed from a dense network of interlaced linear motifs that suggest organic growth or flowing water, rendered in a palette of muted greens, golds, and silvers. The rhythmic web of lead and colour embodies both energy and stillness, an evocation of spiritual renewal appropriate to its placement near the font.

When first unveiled, the windows provoked considerable controversy among parishioners and visitors, many of whom felt that the modern idiom clashed with the thirteenth-century fabric of the cathedral. Yet the work was soon recognised for its sensitivity to the building’s medieval light and its capacity to bridge past and present. The artists’ subtle manipulation of translucency allows the Gothic stonework to remain dominant, while infusing the space with a living radiance that shifts with the daylight.

The Reims transept windows anticipate the collaborations with Marc Chagall that Brigitte Simon and Charles Marq would undertake a decade later for the cathedral’s axial chapel. In these earlier works, their approach is more austere but already reveals their distinctive philosophy, that sacred glass should be an environment of contemplation rather than a surface of narrative. The ensemble stands today as a pivotal moment in the post-war renewal of French stained glass, emblematic of the Simon-Marq workshop’s fusion of heritage craftsmanship and modern expression.

Installed between 1978 and 1981 in the north transept of Reims Cathedral, these monumental grisaille windows by Brigitte Simon and Charles Marq complete the aesthetic dialogue begun with their earlier south transept ensemble of 1961. While the earlier windows explore the vitality of light through colour and linear movement, these later works embody a meditation on purity, material, and the elemental nature of light itself.

Executed entirely in subtle tonal variations of white, grey, and silvered glass, the windows represent the elements of Fire, Earth, and Air, a triptych of creation rendered in abstraction. Their intricate network of engraved and leaded lines suggests shifting natural forms: flame, strata, wind, and water rendered as pure gesture. The treatment of the surface, alternating between transparency, texture, and reflection, allows the northern light to pass through with a quiet, ethereal luminosity, transforming the space into a sanctuary of calm radiance.

By the time of their installation, the controversy that had greeted Simon and Marq’s first modern windows in the cathedral had long subsided. The new grisailles were received with respect and even admiration, seen as harmonising modern sensibility with Gothic architecture through restraint and reverence. In these later works, the artists achieved a fusion of spiritual contemplation and architectural clarity, distilling their mature vision of sacred glass as an instrument of light rather than narrative.

The north transept grisailles stand as a testament to the enduring relationship between the Atelier Simon-Marq and Reims Cathedral, a collaboration spanning centuries, culminating in these late twentieth-century works that reaffirm the cathedral’s identity as both a monument of history and a living vessel of light.