The Western Façade of Saint-Maclou, Rouen

The Church of Saint-Maclou in Rouen (1437–1521) stands as one of the masterpieces of late Gothic architecture in France. Its western façade, executed in the Flamboyant style, unites architecture, sculpture, and theology into a single expression of faith. The façade is a coherent artistic and doctrinal program in three interrelated parts: the architectural composition, the Last Judgement tympanum ⓘ, and the carved wooden porch doors depicting scenes from the Life of Christ. Together, these elements form a visual catechism that guides the viewer from Christ’s earthly ministry to his eternal judgement, embodying the medieval conviction that art, devotion, and salvation are inseparable.

The Western Façade

Constructed between 1437 and 1521, the Church of Saint-Maclou occupies a central place in Rouen’s urban and spiritual landscape. The façade, rising before the narrow medieval streets, is one of the most refined expressions of the Flamboyant Gothic—a style characterized by intricate tracery, dynamic ornament, and an almost musical rhythm of line.

The tripartite composition of the façade, with its three deeply recessed portals, radiating gables, and delicate pinnacles, creates a visual ascent toward the spire that crowns the structure. The interplay of light through the openwork stone transforms mass into movement, suggesting an architecture animated by divine presence.

At its heart, the central portal serves as both architectural and theological focus. Beneath its soaring canopy, the Last Judgement tympanum (mid-15th century) and the carved oak doors (early 16th century) form a unified sequence of images narrating the Christian journey from grace to glory.

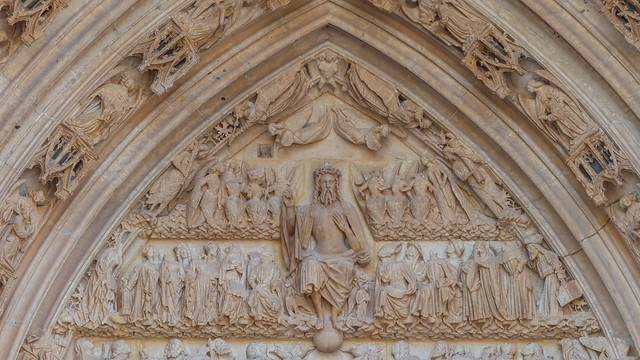

The Tympanum of the Central Portal

The Last Judgement tympanum encapsulates the spiritual climax of the façade’s message. Divided into three registers, it ascends from the awakening of the dead to the celestial court of Christ in Majesty, guiding the faithful from the turmoil of the world to the order of heaven.

The Upper Register: Christ in Majesty

Christ sits enthroned upon a globe, his right hand raised in blessing, his left lowered in judgement. Around him, angels display the Instruments of the Passion, the cross, nails, and crown of thorns, signs of suffering transfigured into victory.

The sculptor balanced grandeur with tenderness: Christ’s calm visage and measured gestures convey both majesty and mercy. The rhythmic arrangement of angels and seraphs creates an aura of unbroken praise, evoking the harmony of the celestial hierarchy.

The Central Register: The Apostolic Witness

Below, the Apostles sit in solemn rows, witnesses to divine justice. Each figure is individualized, some in meditation, others in quiet exchange. Flanking angels sound their trumpets, calling the dead to rise.

This tier symbolises the Church as mediator between heaven and earth, the Apostolic foundation through which the authority of Christ’s judgement is revealed. The sculptor’s balance of symmetry and movement reflects the theological order of salvation itself.

The Lower Register: Resurrection, Salvation, and Damnation

The lowest register presents the resurrection of humankind in dramatic contrast. At Christ’s right, angels guide the elect toward paradise; at his left, demons drag the damned into the jaws of Hell. The carving captures the tension between serenity and terror—salvation and despair. Prophets and patriarchs fill the surrounding archivolts, linking the Last Judgement to its prophetic prefigurations. Once gilded and painted, the entire composition would have shimmered with colour, turning theological doctrine into a vision of living light.

The Porch Doors

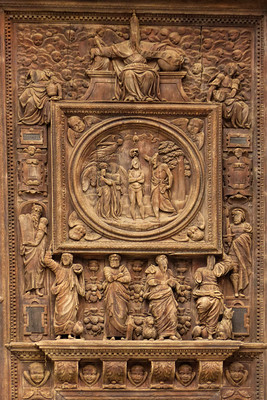

The porch doors of Saint-Maclou form one of the most remarkable ensembles of early sixteenth-century wood sculpture in northern France. Carved between about 1520 and 1525 by Rouen’s master cabinetmakers, they fuse Flamboyant Gothic intricacy with Renaissance compositional order, translating theology into tactile form. Executed as the final major work of the church’s long construction, they extend the doctrinal cycle of the tympanum above, moving from divine judgement to the believer’s lived experience of grace, instruction, and protection.

The doors’ surfaces are structured like miniature façades. Pilasters of saints and foliage frame narrative panels, while tiers of cherubs and grotesques provide rhythmic continuity with the surrounding stone tracery. Ornament and theology intertwine, turning the very threshold into a lesson in salvation.

The Central Doors

The central double doors focus on the redemptive acts of Christ. Each leaf centres on a large roundel: the Last Supper on the left, and the Baptism of Christ on the right. Together they embody the two foundational sacraments of Christian initiation and communion, Eucharist and Baptism, through which the believer enters and is nourished within the Church.

The compositions, dense yet harmonious, reveal a mastery of relief carving. Figures are modelled with Renaissance clarity, their gestures measured and humane. Surrounding foliage of vine and fruit symbolises regeneration and abundance, echoing the eucharistic wine and baptismal water.

Below the medallions, rows of standing apostles and virtues reinforce the doctrinal balance between divine act and human response. The surviving traces of polychromy and gilding would have given the oak a living radiance, transforming the façade into a vision of spiritual vitality. The bronze lion-head knockers at the centre served both function and symbol: the lion, emblem of vigilance and Christ as the “Lion of Judah,” announces the entry into sacred territory.

The Left Door

The left porch door complements the central pair through a more allegorical vision of guidance, teaching, and protection. Rather than repeat Christ’s baptism, it explores the soul’s passage into divine care—an ideal theme for a physical threshold.

The Upper Roundel: Christ the Good Shepherd at the Sheepfold

Within a circular frame, figures gather before a walled enclosure. A calm central figure gestures toward its entrance, while to the right another figure falls backward, excluded from the fold. Above, the Hand of God descends amid angels.

This relief depicts the Parable of the Good Shepherd (John 10:1–9). The fold represents the Church; the standing figure, Christ as both Shepherd and Door; the fallen man, the false shepherd who seeks entry by another way. Carved onto the very door of the church, the image transforms architecture into theology: one passes into salvation through the true gate. The composition thus sanctifies entry itself, uniting the physical act of crossing the threshold with the spiritual passage it signifies.

The Middle Panel: The Lawgiver and the Horned Figures

Below, a prophet or teacher holds a tablet and gestures to it. On either side, horned men turn toward him in dispute. Above, phoenix-like birds symbolise renewal; below, outward-facing cockerels evoke vigilance and repentance.

The scene embodies divine wisdom confronting error. The lawgiver—perhaps Moses—proclaims moral order to rebellious humanity. The birds extend the allegory into cosmic terms: resurrection above, watchfulness below. This framed tableau forms a hinge between revelation and moral action, instructing the faithful in discernment.

The Lowest Register: The Child, the Guardian Angel, and the Centaurs

At the base, at a child’s eye level, a small child is bound to a tree beside a angel, flanked by goat-legged fauns twisting in movement. These hybrids, half human and half beast, are carved with muscular tension and expressive faces. Formerly described as centaurs, they are more accurately fauns—creatures emblematic of sensuality and moral disorder, drawn from late-medieval and Renaissance traditions that associated them with the temptations of the flesh.

The angel’s calm poise and downward gaze contrast the agitation of the fauns, affirming divine guardianship over the vulnerable soul. By the early sixteenth century, devotion to guardian angels was deeply rooted in popular piety, and the sculptor’s decision to place this panel low on the door made its meaning immediate: for children, an image of comfort; for adults, a reminder of grace stooping to meet humanity. The fauns’ restless energy dramatizes the peril that surrounds innocence, while their containment within the relief’s borders signals the victory of divine protection over carnal instinct.

At the bottom of the lower register, two female figures are directly below the bishop on the left and the warrior on the right. They likely personify Faith and Justice (or Ecclesia and Fortitude), serving as the moral foundations of both spiritual and temporal order. Their presence anchors the entire doorway in virtue: the threshold of the church literally rests upon these embodiments of steadfast belief and right action.

Together, the three registers trace a vertical theology of care: Christ guides, the Law teaches, the Angel protects.

Material and Stylistic Unity

The oak carving displays exceptional refinement—deeply undercut foliage, flowing drapery, and rhythmic symmetry showing the hand of Rouen’s finest craftsmen. Renaissance motifs, acanthus, cherub heads, and caryatid saints, blend seamlessly with Gothic energy. The result is a surface alive with motion and meaning, turning craftsmanship into theology.

Meaning and Function

Seen together, the porch doors enact the believer’s spiritual journey.

-

The central doors proclaim salvation through Baptism and Eucharist.

-

The left door shows that grace as guidance, instruction, and protection.

-

Overhead, the Last Judgement tympanum completes the cycle of redemption.

The façade thus forms a visual catechism: from the world into the fold, from ignorance to enlightenment, from peril to divine guardianship. Originally painted and gilded, the doors would have shimmered against the pale stone, transforming passage into prayer.

Conclusion

The porch doors of Saint-Maclou stand as masterpieces of theological sculpture. In them, architecture, scripture, and human touch converge. The central doors proclaim the mysteries of grace; the left door unfolds the moral and spiritual life that follows; and the tympanum above reveals its fulfilment in judgement.

Together they make the act of entering Saint-Maclou a journey through faith itself—Christ guiding, the Law instructing, the Angel protecting, and the Virtues sustaining—a wooden sermon on redemption carved into the very threshold of the Church.