Yahweh and the Early Highlanders

At the end of the Late Bronze Age, around 1200 BCE, the eastern Mediterranean world convulsed. Imperial systems collapsed, Mycenaean palaces burned, Hittite archives fell silent, Egyptian power receded from Canaan. In the central hill country, small farming hamlets appeared where none had existed before. Archaeologists have found hundreds of these sites: stone-built, self-sufficient, rarely larger than a few hectares. Pottery forms, tools, and domestic architecture all belong to the local Canaanite tradition, yet the settlement pattern marks a social re-formation.1

Transhumant beginnings

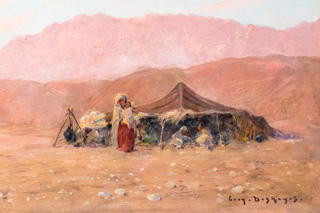

The highlands of Canaan, stretching from the hills of Ephraim to the Judean ridge, offered poor soils but reliable winter rains. Annual precipitation drops sharply with altitude, so communities survived by combining terrace agriculture with seasonal herding. In spring and autumn, clans led their flocks down toward the Jordan Valley or the Shephelah; in the dry summer, they returned to the upland villages.2 This transhumant cycle required flexibility rather than permanent urban life.

The highlands of Canaan, stretching from the hills of Ephraim to the Judean ridge, offered poor soils but reliable winter rains. Annual precipitation drops sharply with altitude, so communities survived by combining terrace agriculture with seasonal herding. In spring and autumn, clans led their flocks down toward the Jordan Valley or the Shephelah; in the dry summer, they returned to the upland villages.2 This transhumant cycle required flexibility rather than permanent urban life.

Such semi-nomadic groups needed a portable religion, a god who moved with the tents. Yahweh, first attested in Egyptian inscriptions from the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BCE as “Yhw of the Shasu,” seems to have been exactly that sort of deity: a desert storm-god of Edom or Seir, worshiped by herders who roamed the southern margins of Canaan.3 When these pastoralists intermingled with sedentary Canaanite villagers, Yahweh’s cult spread northward and fused with that of the high god El. The merger is visible in early Hebrew poetry, where Yahweh is still called El Elyon (“God Most High”) or El of Israel.4

Why pigs disappeared

One of the most distinctive archaeological signatures of these early highland sites is the virtual absence of pig bones. In lowland Canaanite towns, pigs made up 15–20 percent of faunal remains; in the highlands, almost none appear.5 The difference has nothing to do with purity laws, those come centuries later, but with ecology. Pigs require shade and abundant water and cannot be herded long distances; they are useless to mobile herders. Sheep and goats, by contrast, thrive on sparse scrub and are easily transported. The avoidance of pigs began as a practical adaptation to a transhumant economy and was only later recast as divine legislation in Leviticus (c. 539–400 BCE), when the returning priests from Babylonia looked for ways to distinguish Israel from surrounding nations.

Village society and ideology

The highland hamlets were small and egalitarian. Their characteristic four-room houses combined living space and animal stalls, reflecting a household-centered economy.6 Storage jars and terraced fields point to self-sufficiency rather than tribute to a palace. Such communities governed themselves through kin elders, with no central authority. Anthropologists describe them as segmentary societies, held together by shared rituals and reciprocal obligations rather than bureaucratic power.7

Religion served as the moral glue. Altars and simple open-air shrines appear within villages; no great temples are found. Inscriptions and household figurines suggest that Yahweh was worshiped alongside a female deity, likely Asherah.8 These practices were not “idolatry” to the villagers; they were expressions of divine fertility and protection. Only later reformers would label them apostasy.

The theology of movement

Because life in the highlands was mobile and precarious, Yahweh was imagined as a travelling god, one who “went before” his people in battle and journey.9 This conception left deep marks on Israel’s literature. The patriarchs of Genesis are pastoral wanderers; Moses meets God in the wilderness; even the settled monarchy recalls a God who once “marched from Seir” (Judg 5:4). The Israelites’ self-image as a people of journey and covenant mirrors the seasonal rhythms of their ancestors. To move, to settle, to move again, these were not merely economic acts but theological experiences of dependence and promise.

From ecology to identity

By about 1050 BCE, these scattered hill communities had coalesced into a recognizable culture distinguished by its Yahwistic faith, its avoidance of pigs, and its social egalitarianism. They were ethnically Canaanite, linguistically Canaanite, yet ideologically distinct. What began as a set of ecological adaptations, terrace farming, goat herding, portable cults, had become the foundations of a new identity. Yahweh, once one god among many, was now imagined as the exclusive patron of these highland clans. In the crucible of marginal life, the seeds of monotheism were sown.

- 1. Israel Finkelstein and Neil A. Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts (New York: Free Press, 2001), pp. 107–113.

- 2. Avraham Faust, Israel’s Ethnogenesis: Settlement, Interaction, Expansion and Resistance (London: Equinox, 2006), pp. 43–50.

- 3. Kenneth A. Kitchen, “Shasu of Yhw,” in Ramesside Inscriptions, vol. 2 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999), p. 74.

- 4. Mark S. Smith, The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), pp. 33–41.

- 5. William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), pp. 88–96.

- 6. Israel Finkelstein, The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1988), pp. 314–322.

- 7. Norman K. Gottwald, The Tribes of Yahweh (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1979), pp. 201–219.

- 8. J. T. Milgrom, “The Asherah of Yahweh,” Biblical Archaeologist 45 (1982): 1–10.

- 9. Frank Moore Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973), pp. 41–75.